Existing Patients

(732) 875-3814

New Patients

(732) 334-6374

Spinal fusion is a surgical technique used to join two or more vertebrae so they heal into a single, solid bone. By eliminating motion at a painful or unstable segment of the spine, fusion reduces mechanical irritation and can relieve symptoms such as localized pain, nerve-related pain, and weakness. Surgeons perform fusion in different regions of the spine; when performed in the neck it is called cervical fusion, and when done in the lower back it is called lumbar fusion.

Although the basic goal is straightforward—create stability where instability exists—the approach varies depending on anatomy, diagnosis, and patient needs. Surgeons may access the spine from the front, back, or side and use different combinations of bone grafts and implants to encourage the vertebrae to grow together. Advances in imaging and minimally invasive tools have improved the precision of these procedures, helping to preserve surrounding soft tissues while achieving reliable fusion.

For people who have exhausted conservative options and continue to have progressive symptoms, fusion can be an effective way to restore function and reduce pain. The decision to fuse is individualized, taking into account the location of the problem, the degree of instability or deformity, and the patient’s overall health and goals.

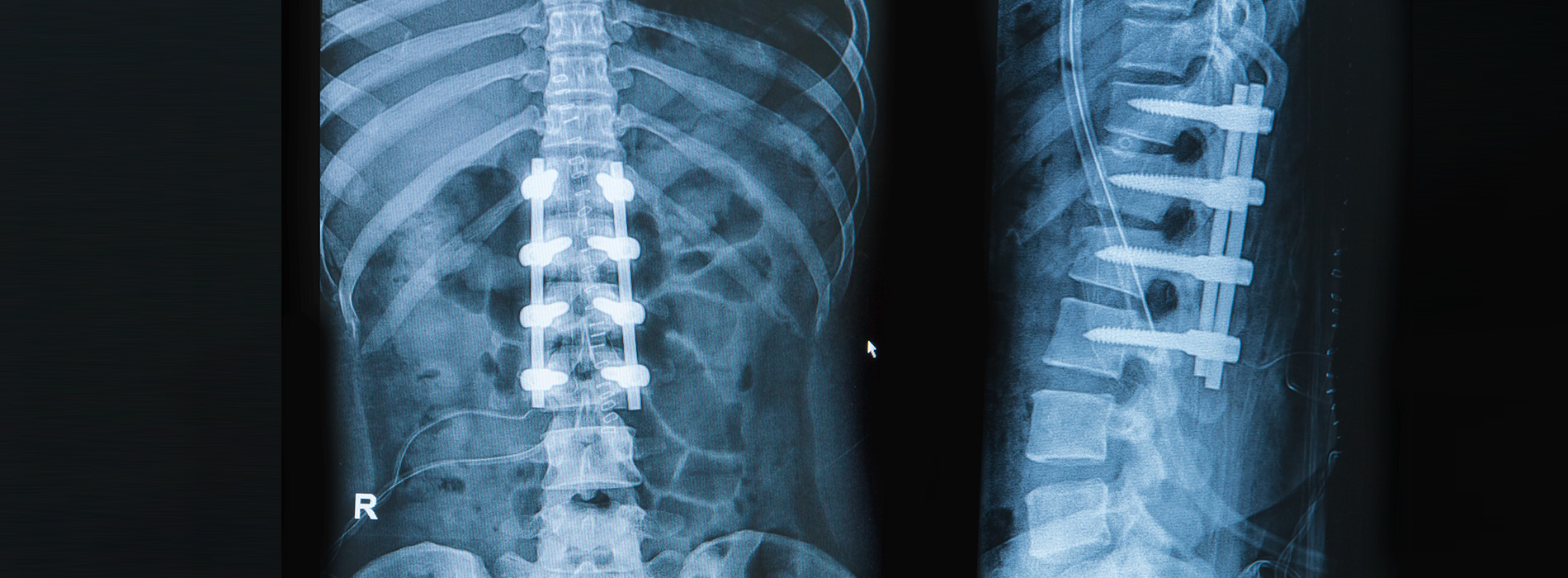

At its core, fusion replaces a painful, moving spinal segment with a stable construct that relies on bone healing. Surgeons commonly place a graft between vertebrae and secure the area with hardware—such as screws, rods, or plates—to maintain alignment during the healing process. Over time the graft incorporates and the vertebrae fuse into one solid mass, which stops abnormal motion that has been contributing to symptoms.

Fusion is not intended to restore degenerated discs to their youthful state; instead, it addresses the consequences of degeneration such as instability, deformity, or repeated nerve compression. When successful, patients typically experience a reduction in pain from mechanical sources and improved ability to perform daily activities that were limited by discomfort or weakness.

Fusion is most often considered when structural problems in the spine are the primary driver of symptoms. Typical indications include severe degenerative disc disease with instability, spinal fractures that compromise alignment, certain deformities such as progressive scoliosis, and cases where prior surgeries have failed to provide a durable result. Nerve compression accompanied by mechanical instability is another common scenario where fusion is recommended.

Careful candidate selection is crucial. We evaluate each patient’s symptoms, physical exam findings, and imaging studies to identify whether fusion will address the root cause of their pain. Nonoperative measures—such as physical therapy, activity modification, medication management, and targeted injections—are usually tried first unless the condition is urgent or neurological function is rapidly declining.

Medical factors like smoking, uncontrolled diabetes, or osteoporosis affect healing and are taken into account when planning surgery. When appropriate, surgeons work with patients to optimize overall health before proceeding so that the odds of a successful fusion and smooth recovery are maximized.

Fusion is typically recommended when there is clear evidence that abnormal motion, deformity, or structural collapse is the major cause of pain or neurological symptoms. For example, a vertebral fracture that produces instability, or a disc that has degenerated to the point that it allows abnormal motion and pinches nerves, are situations where fusion provides a structural solution.

In many cases, diagnostic imaging such as X-rays with flexion-extension views, CT scans, and MRIs help demonstrate the degree of instability or nerve compression. These findings, combined with the patient’s symptoms and functional limitations, guide the recommendation for fusion versus continued conservative care or alternative procedures.

Surgical planning begins well before the operating room. The surgeon selects the safest and most effective approach—anterior (from the front), posterior (from the back), lateral (from the side), or a combination—based on the level of the spine involved and the specific pathology. Modern techniques often use specialized retractors, microscopes, and navigation tools to minimize tissue disruption and improve implant placement accuracy.

During the procedure, bone graft material is placed between the vertebrae to promote new bone growth. This graft can come from the patient (autograft), a donor source (allograft), or synthetics and biologic enhancers that support fusion. Metal implants such as screws and rods or plates are used to hold the spinal segment in the desired position while the graft heals. In many cases, instrumentation also restores or preserves spinal alignment.

Patients usually spend one to several days in the hospital depending on the complexity of the surgery and their medical needs. Pain control, early mobilization with guidance from physical therapy, and measures to prevent complications like infection and blood clots are key components of postoperative care. Education about safe movements and activity restrictions helps protect the fusion as it begins to form.

Most fusion surgeries follow common stages: exposure of the spine, preparation of the bone surfaces, placement of graft material, and application of fixation devices to maintain alignment. Many surgeons now incorporate image guidance, minimally invasive retractors, and intraoperative monitoring to increase safety and accuracy. These tools allow precise implant placement and reduce risk to nearby nerves and tissues.

The choice of graft and hardware is tailored to each patient. Biologics and bone substitutes can accelerate fusion in some cases, and the use of robust fixation allows earlier mobilization in the postoperative period while the graft consolidates into solid bone.

Recovery from fusion is gradual. In the first weeks after surgery the focus is on pain management, wound care, and safe mobilization. Most patients begin light walking the day of or day after surgery, with supervised progression of activities. Formal physical therapy typically begins a few weeks after surgery to restore strength, flexibility, and movement patterns that protect the fused and adjacent segments.

Long-term outcomes depend on the underlying condition treated, the number of levels fused, and how well patients follow rehabilitation guidance. Many individuals experience meaningful reductions in pain and functional improvement, enabling them to return to work and recreation with fewer restrictions. It’s important to have realistic expectations: fusion stabilizes a painful segment, but it does not rewind aging or prevent future degeneration elsewhere in the spine.

Follow-up imaging is used to confirm that fusion is progressing. Patients are encouraged to maintain a healthy lifestyle, including smoking cessation and appropriate conditioning, to support bone health and overall outcomes.

Signs that recovery is progressing well include steadily decreasing pain with activity, improved ability to perform daily tasks, and evidence of bone healing on follow-up X-rays or CT scans. Persistent or worsening neurological symptoms, increasing pain, or signs of infection warrant prompt evaluation. Regular check-ins with the surgical team help ensure any concerns are addressed early.

All surgeries carry risks, and spinal fusion is no exception. Potential complications include infection, bleeding, nerve irritation, nonunion (failure of the bones to fuse), and hardware-related issues. The surgical team mitigates these risks through careful patient selection, meticulous technique, and comprehensive postoperative care. When non-surgical options are likely to control symptoms, those approaches are preferred before considering fusion.

Alternatives to fusion may include targeted decompression without fusion, motion-preserving procedures such as disc replacement in select cases, or ongoing conservative care. The right choice depends on the specific diagnosis and the patient’s goals. Discussing the benefits and trade-offs of each option ensures the chosen path aligns with what matters most to the patient.

Receiving care from a multidisciplinary team familiar with both the technical and rehabilitative aspects of spine surgery helps optimize outcomes. At the Brain and Spine Institute of New York and New Jersey, our approach emphasizes individualized planning, the use of advanced techniques, and coordination with rehabilitation specialists to support a safe recovery and meaningful functional improvement.

In summary, lumbar and cervical fusion are established surgical options for treating spinal instability, deformity, and certain forms of nerve compression. They offer a structural solution when conservative care is insufficient and are planned carefully to align with each patient’s needs. If you would like more information about whether fusion may be appropriate for you, please contact us to discuss your situation and next steps.

Spinal fusion is a surgical procedure that joins two or more vertebrae to stop abnormal motion between them and restore stability to the spine.

The operation commonly uses bone grafts and fixation devices such as screws and rods to hold the vertebrae in position while new bone grows across the treated segment, creating a single solid bone over time.

Fusion is typically recommended when spinal instability, severe degenerative disc disease, fractures, deformity or recurrent nerve compression causes persistent pain or neurological symptoms that do not respond to conservative care.

Decisions about recommending fusion are based on clinical findings, imaging studies and a patient’s functional goals, and Dr. Arien Smith applies advanced techniques to balance stabilization with tissue preservation.

Lumbar fusion addresses conditions in the lower back and is designed to reduce pain from nerve irritation, instability or deformity affecting the lumbar segments, while cervical fusion targets the neck where mobility and protection of the spinal cord are primary concerns.

Approaches, instrumentation and postoperative precautions differ between the two regions because of anatomical considerations, but both procedures share the same goal of stabilizing the spine and promoting bone healing across the treated levels.

Spinal fusion can be performed through posterior, anterior or lateral approaches depending on the location and nature of the problem; each approach provides specific access to the disc space and vertebral bodies and may be combined with instrumentation for stability.

Minimally invasive techniques use smaller incisions and muscle-sparing methods to reduce blood loss, shorten hospital stay and speed recovery while still allowing placement of grafts and hardware when appropriate.

Bone graft options include autograft (patient bone), allograft (donor bone) and synthetic or biologic substitutes that promote bone growth, and surgeons select the best option based on patient factors and the size of the fusion required.

Hardware commonly includes screws, rods, plates and interbody cages that support alignment and compress the grafted area to encourage fusion, and implant selection is tailored to anatomy, bone quality and the surgical approach.

Initial recovery usually involves a brief hospital stay for pain control, wound monitoring and early mobilization; patients are instructed in safe movement patterns and activity restrictions to protect the fusion while bone healing begins.

Rehabilitation commonly includes a gradual progression of activity and a structured physical therapy program to restore strength and flexibility, with many patients returning to routine activities over weeks to months depending on the level and extent of the fusion.

As with any surgery, fusion carries risks such as infection, bleeding, nerve injury, blood clots and reactions to anesthesia, and there are procedure-specific concerns like nonunion (pseudoarthrosis) where the bones do not fuse as intended.

Long-term considerations include adjacent segment degeneration where levels above or below the fusion may develop increased stress over time, and the surgical team discusses these risks and strategies to minimize them during preoperative planning.

Many patients try conservative treatments before fusion, including physical therapy, targeted injections, medication management and activity modification, which can relieve symptoms and improve function in suitable cases.

For selected patients, motion-preserving procedures such as disc replacement or limited decompression may be alternatives to fusion, and the choice depends on the diagnosis, anatomy and long-term goals discussed with the surgeon.

Preoperative evaluation includes a thorough history and physical exam, targeted imaging such as X-rays, MRI or CT scans, and assessments of medical comorbidities to optimize safety and outcomes.

The surgical plan addresses which levels require fusion, the approach, graft and implant choices, and perioperative strategies for pain control and rehabilitation, and this individualized plan is explained in detail during consultations at the Brain and Spine Institute of New York and New Jersey.

Once solid fusion is achieved, many patients experience durable pain relief and improved function, though the timeline for complete fusion varies and routine follow-up imaging is used to confirm bone healing and implant position.

Long-term management focuses on maintaining spinal health through weight management, core strengthening and avoiding high-risk activities, and the surgical team provides guidance on safe activity progression and return-to-work planning following recovery.